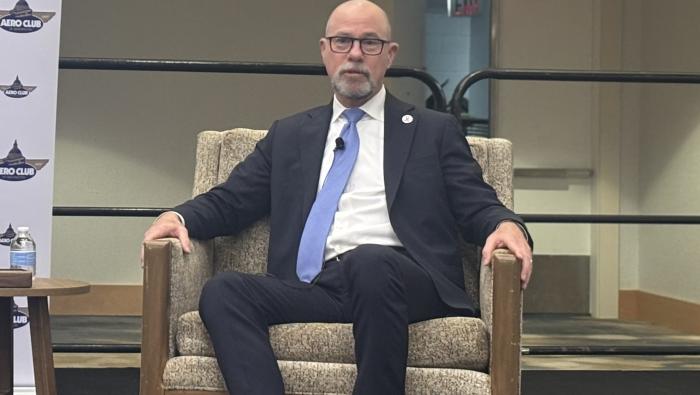

FAA expecting more summer gridlock

by Paul Lowe

Hoping to stave off aviation gridlock this summer, the FAA last month summoned 60 participants from major and regional airlines, pilot an

Hoping to stave off aviation gridlock this summer, the FAA last month summoned 60 participants from major and regional airlines, pilot an